Singing Along to Queen’s Retcon at The Garden

People do not believe this anymore, but Queen could not get arrested in America.

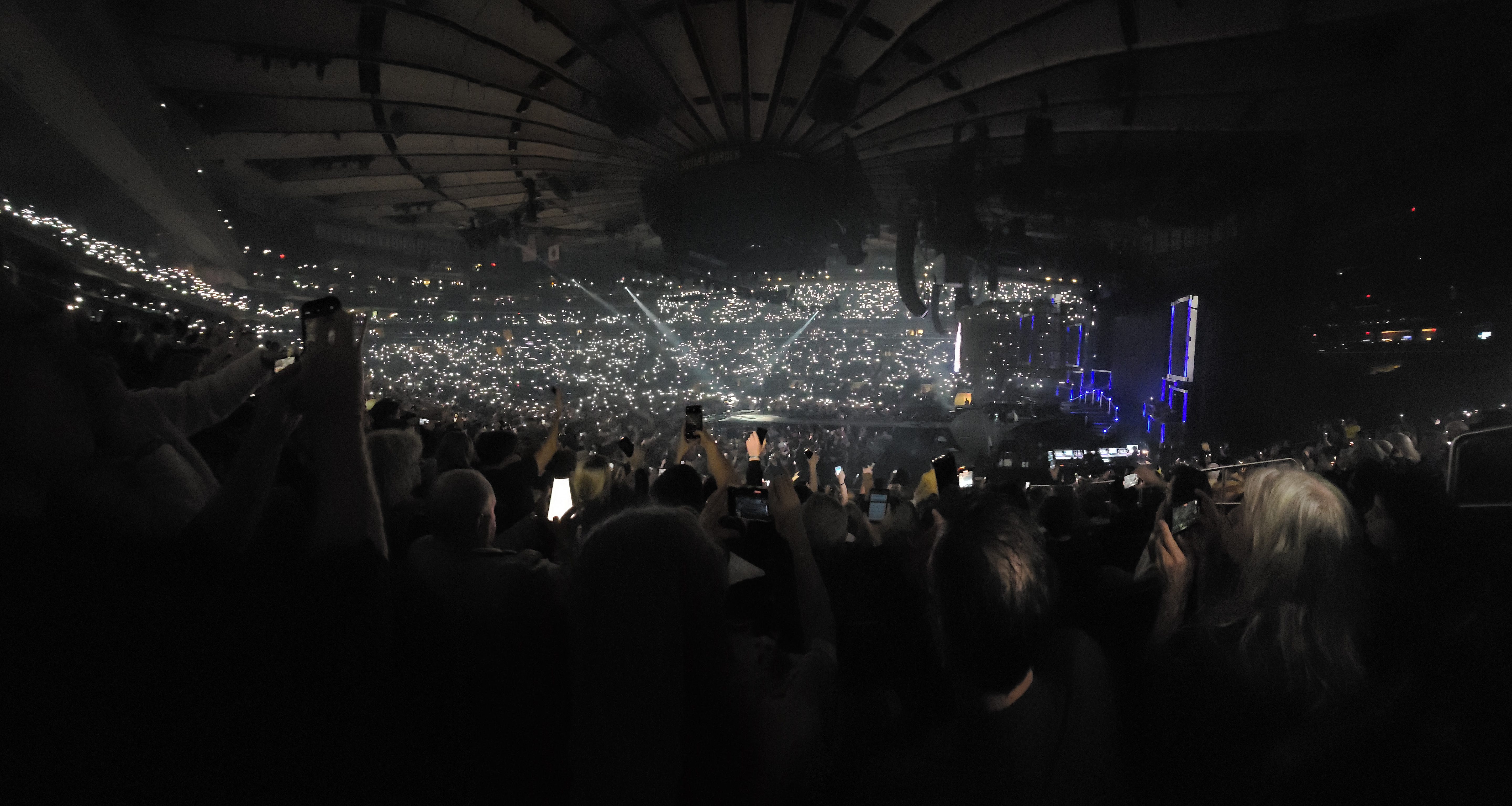

A couple weeks ago I went, alone, to see Queen + Adam Lambert at Madison Square Garden.

In my old age, I love going to concerts alone. There’s no talking anyone into going, no making arrangements for what dates work or who can get off work. I can get much better seats. And then, at the show, I don’t need to wonder if the other person is having a good time. I can just listen to the music.

In the case of this particular concert, the sold-out MSG tickets were also exceedingly expensive. It was the tenth time over four tours I had seen Queen + Adam Lambert, and so this time around, it also seemed like the fiscally responsible thing to do.

In previous Queen + tours with Paul Rodgers and Adam Lambert, I’d go to multiple shows each tour: one show with friends, another with wifey, and one by myself. Last tour, I brought the girls to one gig as well. This time around, I figured I could go with whoever I wanted, or just go alone.

One of the pleasures of getting old is not caring about being alone for these things.

Alone, I let myself react the way I want to react. For example, on just about every Queen show, towards the end of “Under Pressure,” which is sung by Adam Lambert and Queen drummer Roger Taylor, I allow myself to cry.

I don’t cry the whole song—I cry just when the song turns the corner to the outro: “Because love’s such an old fashioned word/and love dares you to care for/the people on the edge of the night…”

You know, that part.

In some mixes of the song—there are several—you can hear Roger Taylor singing in the original, that high Rod Stewart-type rasp of a voice wraps around the voices of Freddie Mercury and David Bowie. Whenever I witness that happening, I start to exit my body a bit. I am suddenly 14 again, listening to that song for the first time on the radio. I also stop to think for a moment how freaking strange the song is, from the arrangement to the snaps and electronic claps and shimmery guitar. And of course that bass part.

Wait—I think I start to cry earlier in the song. It’s when Freddie sings “Can’t we give love that one more chance” and Roger sounds like Keith Moon.

By the time we get to the “this is our last dance” part, I am in full waterworks mode, and nobody needs to be around when that happens. There’s no stopping me doing it, the crying, unless I head off the merch table. And so cry I will.

The strange part of seeing Queen in 2023 is how many of the songs—big songs, not dip-out-to-get-merch songs, but anthemic showstoppers—were not played on the radio when they were first released. At least not in the United States. And yet, there I was, in New York City, singing along to “Who Wants to Live Forever” and “The Show Must Go On,” songs that came and went without so much as a blip on the radio or MTV.

Half of their setlist included songs that were flops when they first came out. The concert opened with the arena doing those handclaps to “Radio Ga Ga” for crying out loud. All of those songs I just mentioned did not dent the top 10, let alone the top 40. Back when they were released, they flopped.

The only time I could have possibly seen my favorite band in the whole world—Queen, if you’re keeping up here—with its original singer was on July 24, 1982. I was 14, about to start my freshman year at Camden Catholic High School. Since I was 12, I bought all their records with the pay I had working for the janitor at Our Lady of Perpetual Help. The Game album had two #1 singles, “Another One Bites The Dust” and “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” Shortly thereafter came the Greatest Hits album and “Under Pressure.” Queen were, from 1980-1981, about as popular as they could be in the United States.

The previous May, I’d bought the band’s newest record, Hot Space, the day it came out. I listened to it and memorized it before I realized that no one else was doing it. Music news didn’t spread so fast in those days, and it was inconceivable to me that Queen had a flop record. But it was a flop. Sure, “Body Language” got some airplay. But rock fans, especially American rock fans, hated anything disco, and even though Hot Space wasn’t all disco, it has enough of it to count. The concert I wanted to go to but did not, at Philadelphia’s Spectrum, failed to sell out.

I didn’t even know how to buy tickets for a concert. I didn’t even know people who went to concerts, let alone how often or regularly recording artists would swing into town for them. So when I couldn’t rope an aunt or uncle or friend of an aunt or uncle to take me to the Queen concert, featuring opening act Billy Squier, I just thought there would be another chance. The band’s appearance on Saturday Night Live in September 1982, marked the last time Freddie Mercury played on North America soil.

After 1983, my favorite band in the whole wide world, previously popular, was no longer popular in the United States. The singles that hit #1 all around the world barely dented the charts in the United States. Queen’s last chart hit, “Radio Gaga” peaked at #16 on Billboard’s Hot 100. After that it’s Queen’s flop era.

People do not believe this anymore, but Queen could not get arrested in America.

Queen videos were played maybe once on MTV, usually late at night. Queen’s last two world tours did not include the U.S.

They stopped touring altogether in 1986. Freddie died in 1991. I never got my chance to hear him sing, which I suppose would call one of my life’s biggest omissions.

What happened in those years, from 1982 to, say, 2002, was that my fandom turned more personal, even secretive. No one around me was exactly bopping along to “Hammer to Fall” or “Who Wants to Live Forever.” I obsessed over every news clipping, every piece of music the band put out, from solo records to guest spots on other people’s songs. Did you know Jeffrey Osbourne’s “Stay With Me Tonight” features a Brian May guitar solo?

I loved other bands, for example R.E.M., and got to sing along with thousands of people in smaller places and then bigger places. I got to know what it was like to be a fan of a band that had a passionate following. When it came to Queen, however, it was different. It sounds absurd to say it now, but I listened to Queen by myself. I cleared out parties when I slapped Roger Taylor solo albums on the turntable. I guess I still do, but you get my point.

When I wrote my first two books about my Queen fandom that came out in 2003 and 2004, the point of view reflected that underdog, even alienated fandom. I now think it’s a kind of gift I never got to see Queen live or live in an alternate universe (i.e., the rest of the world) where the band remained popular. To have done so would have made me a different person.

Back in 1997, when being a Queen fan in North America was still a cult enterprise, I came across a letter from Queen guitarist Brian May to a fan, reprinted in News Of The World, a fanzine for other North American fans like myself who were keeping the flame.

In it, Brian explained why Queen “gave up” on America after 1982. It’s a long letter, typed in Queen letterhead. The explanation is detailed, and includes some things that are still used as narrative shorthand in the band’s history. Queen were perceived as going disco. There was a big payola scandal at the time. One of their managers—Paul Prenter, the villain in the Freddie Mercury biopic—alienated radio people. They wore drag in the “I Want to Break Free” video, which MTV banned. And lastly, the band, Freddie especially, were not ready to eat humble pie and go back to playing theaters after filling arenas everywhere else. Even after Wayne’s World and that famous “Bohemian Rhapsody” scene, even after Freddie died, the U.S. didn’t entirely get back in line with the rest of the world.

The result, Brian wrote, is that “[t]here is a huge chunk of Queen Music which rang in everyone’s ears from Budapest to Benos Aires [sic] to Beijing, but was silent in America. That can never be changed now.”

It did change, over time. Certainly the Freddie movie played a big part, and brought loads of new fans. I liked the movie and even cried while watching it.

I like to think the songs had something to do with it, too.

Back in 2006, Brian May and Roger Taylor did the unthinkable: they played live as Queen, with Paul Rodgers. They did a couple European things, the Brit Awards, and then did two U.S. dates: one in Los Angeles and one in New Jersey. It had been 24 years since the last time anything calling itself Queen played in the United States. The band were testing the waters to see if anyone was interested.

I don’t know if the concert sold out, but it was full enough. It was as much of a fan club convention as it was a concert—people flew in from the Midwest and Florida and Massachusetts.

Queen + Paul Rodgers did do a U.S. tour the next year, and those were great shows. They played secondary arenas in places like Worcester and Nassau in Long Island. The sold-out Madison Square Garden shows would come later.

And you know who made it happen, in large part? Adam Lambert.

We used to watch American Idol when it was super popular, and it just seemed to be the obvious thing that Adam Lambert was genetically engineered to sing Queen—all of the songs, including “Killer Queen” and “Don’t Stop Me Now,” which would have sounded absurd from Paul Rodgers’ microphone.

I thought Lambert would sing in the We Will Rock You musical—which is maybe the one project in all of Queen-dom. But this is much better.

Most of the hardcore Queen fans I encounter online think of him as someone to be tolerated, what with his campy histrionics and outfits and singing those songs in their original keys and hitting high notes that Freddie hit in the studio but didn’t try for in concert. The old fans want a Freddie Mercury soundalike or impersonator, and it’s kind of sad. The old fans still have to deal with how much gay camp figures into Queen’s appeal.

The new fans just sing along.

I was wrong. Queen did play as Queen in the U.S. once, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 2003. It took place in the Waldorf Astoria. I snuck in, and got to see Roger Taylor’s bass drum onstage before security threw me out. I escaped in a laundry cart down a service elevator, just before Jann Wenner walked up to the podium to start the concert.

I’m going overboard these days with a term I learned a couple years back: retcon. Short for retroactive continuity, it describes a world that is changed to adjust the present. I’m probably wrong, but I think of retcon as a first cousin of simulacra, an idea I learned from Jean Baudrillard, which is the copy of something that never existed or is not real, like parts of Disneyland or famous writer’s homes outfitted with period furniture.

In the case of Queen, the retcon means all those singles the band put out in the 1980s that flopped in the United States are now part of our songbook. When I was was singing along to “I Want It All” at Madison Square Garden with 20,000 other people, it is hard to think that same song fizzled at #50 on the charts in 1989. The Queen retcon makes up for more than a decade of, if not failure, then certainly flops.

It sort of freaks me out and also continues to make me very happy, after all these years, to sing along to Queen flops with other people.