Mom’s birthday came and went last week. Grief doesn’t follow a calendar, but still.

I don’t know how many sentences I’ve read over the years that begin this way: “The thing about grief is….” But it’s a lot.

There are two kinds of humans: people who make generalizations about people, and people who don’t.

There are two kinds of writers: successful ones who make third-person-plural “we” statements, and the unsuccessful ones.

The sentences above are all attempts to begin this. None of them seem to work.

Call me an unsuccessful writer.

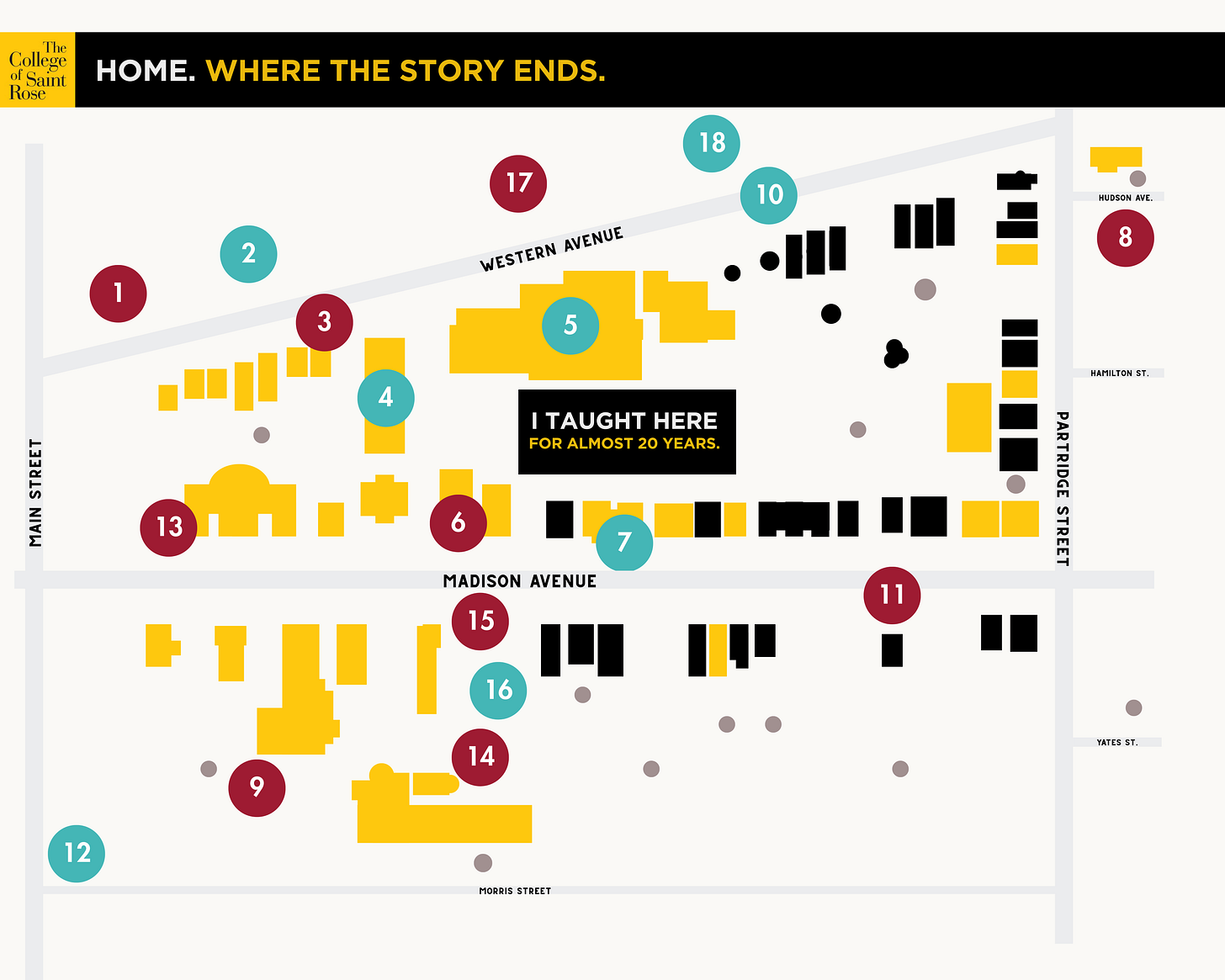

In my classes, I gave students models for their writing. “Make Your Own” assignments.

The one I like the best is “Make Your Own ‘White Album,’” which is modeled after Joan Didion’s essay “The White Album,” the title essay from her book with the same name. If you haven’t read it you should. It’s one of my all—time favorite.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live” is how it opens.

See? First-person plural, confident. I love that. If I couldn’t be confident, the least I could do as a teacher was for my students to feel that.

It was sometimes a battle to get students to write in the first person plural. It sounds oddly formal, for one thing. Do it one way, and you might sound like a priest giving a boring homily. Quite often, the early drafts would sound like Meredith’s voiceover narration in Grey’s Anatomy. “Sometimes, what we want is exactly what we need” or something like that.

I’m not yet used to seeing images of mom on Facebook or wherever and not reflexively sharing it or liking or making some funny comment about it.

One of the many shitty and cruel parts of being old and terminally online is that memories pop up of people who have gone: memories, throwbacks, “on this day” posts. Instead, my hand hovers over the phone screen or mouse, and I take a moment looking at the screen.

This will happen waiting in line for coffee or at work. And then I have to get on with whatever it is that I was trying to do.

Another Make Your Own assignment was modeled on “Variations on Grief,” an essay by Megan Daum. It’s been described as a “savage self-indictment,” but that only explains it in part.

Reading “Variations on Grief” over the years has given me the courage to not be the hero in my own writing and to urge my students to do the same. Sometimes I really am the villain, or at least the antagonist as well as the protagonist, in my own stories. That’s just a fact.

It’s not just important to offer up all sides of oneself in personal narrative, I told my students. It’s absolutely necessary. You may find that, in making yourself unsympathetic, you will make more connections with readers than if you portrayed yourself as the perfect everyperson main character, so common in mainstream film.

Here’s the thing: I don’t feel like being unsympathetic when I write about mom. That’s just shitty.

What I will say is that me and mom had our battles over the years, but she and I stuck it out. That’s what matters.

When I was in my twenties, trying to figure out what to do after graduating college—a first in my family—I poked around at jobs. I was torn about defining myself as a writer, despite encouragement from teachers and other writers. I wasn’t even approaching being a capable writer back then, but I wanted to be a writer so badly, on a level I don’t think I’ve ever felt again. And I think that’s because I was trying to define myself as well as learn a whole craft.

And so here I am, years later, a writer and writer alone, no struggle or hope, no ambition to speak of, writing about my dead mom.

My aunts and sister might be reading this and think it’s cruel of me to write “dead mom.” I don’t want them to feel that way.

It’s just that writing “dead mom” is the shortest, most effective and yes, maybe the most cruel way to get my point across. If you have a dead mom, you might get what I am saying here. If I wanted to let someone know I don’t feel so great or to leave me alone, I reserve the right to say “I’m just thinking about my dead mom right now—can you please buzz off?”

Mom would approve. Mom didn’t mince words.

Some specifics, from mom’s obituary, which I wrote:

Patti was known for many things: Jean Nate After Bath Splash, hot rollers, and prodding her sister Chrissy to wrap up long grace prayers before Thanksgiving dinner. She loved the taste of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky, the hunkiness of Tom Selleck’s mustache, and the soulful sounds of Michael McDonald’s voice. She had a random dislike of actor Jeff Bridges and garlic. She ironed every outfit she ever wore and put on make-up every day. She called everyone “honey.”

This is not just about my dead mom, but how I am trying to get something out here, in these words, so I don’t have to carry it around all the fucking time.

A couple weeks ago, things were sucking in my day-to-day. I was piling on the worry about the future, worried about my kids in ways only catastrophizing parents can do, thinking about how so many items of my writing career wish list were gone. And then, my mind, aided by a little “Caroline No” on the car stereo, brought out the big one: mom isn’t here. There’s no one to call and have a meandering conversation that adds perspective to the day. The exhaustion. The eyes on the verge. The quivering mouth.

And then, next song, next red light. Gone.

This is about my grief. Or at least defining it for myself. When our dad died more than ten years ago, writing about that felt like working up myself into some sort of feeling, an approximation of what we could call grief. Grief as an absence, a man who I loved as a child and hated as a man. Trauma-dumping, as the kids say these days.

That writing-as-performance style is all over the bookstores these days, lyric essayists who think they’re chopping up experience like some J. Dilla. It often comes from a place of privilege, sidestepping real stories because it might expose the comfort underneath. I know I am being cruel, catty even. But when it comes to grief, my grief, it’s about telling stories. It’s a working class thing I grew up with, and I miss it. I hate that I broke from it so hard, dismissed it as some bullshit superstition.

That cardinal outside is mom giving us a sign.

I just talked to her in a dream.

She’s right here, at the bar, doing a shot with me.

Some more specifics:

Friends and family remember her as hilarious. She would mug for the camera next to statues and signs. She would often, at formal gatherings, contract a case of the giggles. From honors inductions ceremonies, funerals, and poetry readings to student concert recitals and one yoga class in the 1970s, Patti would often send others into suppressed, simpering laughter.

In the top drawer of my desk is the yellow procession flag from mom’s funeral. I clipped it to our car with FUNERAL facing the front as we auto-processioned from church to gravesite. I keep it in my desk folded in half to say FUN. Put the fun in funerals, she’d say. I’d like to think she’d get the joke.

Mom’s birthday landed on a workday, and because of that I tried not to think about it. It was impossible. After a particularly stressful day, where I navigated unfamiliar people in an unfamiliar office doing unfamiliar things, I would have called mom and wished her a happy birthday, and we would have talked about pretty much everything. I can’t say, hypothetically, that mom would have given great advice, but her response would have put whatever was riling me up into some sort of perspective.

She would give me an account of some of her celebrations. Her sisters would have taken her out, a diner or some place fancier. The group would include props, sight gags, pointing to some sign or menu item with a funny name. My sister might have dragged her out to Philly with Bill to get margaritas or happy hour karaoke thing in Philly, some situation in which Patti a bar full of people might sing “Happy Birthday.”

Photos would be posted of mom both in and out of her element. A statue of an animal or rodeo ride. These celebrations would begat stories of her interactions with the outside, non-mom world. Mom had this ineffable quality, one completely without any guile but also arch. Think Bea Arthur meets Dana Carvey’s Church Lady.

Everything she said seemed like a joke set-up. It was never clear, for example, when she asked a waiter how big the sausage was, whether she meant to be funny or it just sounded that way. When one waiter responded I’ve never had any complaints, her generous laughter won over another human, who now had a story to tell, to dine out on.

I miss her, is what I am saying. The world is way less fun and less loving without her.

This is about defining grief and it is also about lying about it. I know, I know: whole books are written about grief. I get recommendations all the time. I am sure I will connect with one some day.

But right now at least, I feel selfish talking about myself, so much so that mom is obscured by my story.

When I wrote about growing up, I thought it would be all about my dad, this extraordinarily complicated man who left my life just as I was becoming a man myself. I thought of my hometown as the secondary character.

I thought I had my situation and my story, as Vivian Gornick calls it. I had the place and I had the ideas.

But I forgot about one thing: a hero.

And that hero was mom. It took my sister to shake that out of me. Allow me to quote from my own writing again:

“I guess I am still wondering how we turned out the way we did,” I said.

“You’re forgetting we had Mom. She filled in all the cracks and voids as best she could.”

As I type about my dead mom, I’m distracted by a New Yorker podcast playing in the background. David Remnick interviews a writer about his memoir on his family’s frozen vegetable empire they created in “Southern New Jersey.”

Nobody ever says Southern New Jersey except for people like David Remnick, bless his heart.

“There must be a sense of some profound satisfaction telling this story,” the editor asks, a softball if there ever was one. The writer, who seems like a nice person, demurs, then talks about the privileges his daughter has because of exploiting people of color while building a frozen vegetable empire.

I think about writing my own family’s story, how I would have this voice in my head, one echoed by agents and publishers, that would say no one really wants to hear about a blue collar family from South Jersey. They want to read about people they want to be.

For example, people from a rich family that ran a frozen vegetable empire in Southern New Jersey.

Would people really want to read about the woman who danced with one of the Righteous Brothers at the Latin Casino? Or as a 19-year-old typed 95 words a minute and dodged getting goosed in the hallways at a Center City Bank? Or the divorced mom who rubbed shoulders with Eric Lindros typing memos for the owner of the Philadelphia Flyers in a pre-gentrified Fishtown?

Hearing this interview reminds me of another book, one my old press put out. The memoirist, a scion of a beer brewing family, experiences “great privilege” and “shopping trips to London and New York” with their family, only to have it collapse after the people buying the beer lose their jobs. Drug habits and divorce follow.

These books feel familiar—they hook us with a romance of capitalism, a reminder to readers that they, too, might have been rich once. We see versions of ourselves in writers warped by self-assurance and the need to impress no one but themselves.

That these books by robber baron descendants get published at all makes me shrug. It’s the way mom would after hearing about people who never worked a day in their lives.

I write this on a weekend, yet another day that drives home that she is not around any more. Another idle Sunday afternoon where I’d call and check in. She was the last person I would have an epic phone conversation with. There were times when, as I said goodbye to her after talking about everything under the sun, I’d say goodbye and look at the total call time.

She’s still in my phone contacts, so I can give you selected dates and times: February 29, 2024, 20 minutes, 9 seconds; August 17, 2023 33 minutes and 34 seconds; July 21, 2023: 36 minutes, 48 seconds;

Mom was a storyteller. She’d give a debrief on the family goings-on in ways that connected back generations. She’d invoke my dad, who I didn’t speak to in the last 20 years of his life, in the oddest of moments, and was the only time I would hear about him and, instead of wincing from rejection, add to a memory, laugh.

Putting the “fun” in funeral. It’s the only way.

For her birthday, I shared a photo on Instagram of mom with our girls from ten years ago. The photo, taken in a rental in Sea Isle City, is filled with white furniture and prints of seagulls. Both girls climb on top of Grandma Patti like a jungle jim, no doubt asking about going to the custard stand or a trip to the boardwalk. Patti sits in full makeup and hair done up, a queen in all her glory. When I think of mom I think of her in this state, surrounded by grandchildren, ready to hit the boardwalk and stand in the smoking zone with a Marlboro Light 100.

I don’t have a metaphor for mother-son relationships. Our relationship petered out with Husband Number Two and blossomed with Bill, Husband Number Three. What all three husbands had in common is they had their own nerdy interests. They had and have past pain in their lives, and coped with routine and keeping themselves busy with hobbies, collections. Sound familiar? It does as I look around at a roomful of books and records and several thrift shop amateur paintings by a retired lawyer from Connecticut I love to show off to visitors.

Mom took in men and took care of them, myself included.

What I mean to say: I miss her so much I don’t know how to end this sentence.

Maybe that’s what grief is: a fragment, a dangling modifier looking for a subject.

Or maybe grief is a gerund. Grieving: too slippery to be a noun, too never-ending to work as real action. And I fucking hate gerunds.

Thanks for subscribing, and for reading.

I do apologize in advance for any typos. They drive me crazy when I spot them after I send this out.

Or, you know, maybe just buy me a coffee. I love coffee.